‘Timing is everything’ may well have been Albert Sherbourne Le Souef’s favourite adage. The man, a rabid animal lover – born at Melbourne Zoo – had found his moment in history among an era of great change.

In 1901, colonial Australia was no longer six British territories, but one nation. With this unification came a feeling of being a more powerful and significant part of the world.

Australian women took to the suffragette movement like moths to a flame that already burned bright overseas, demanding equal rights, including the right to vote and stand in elections.

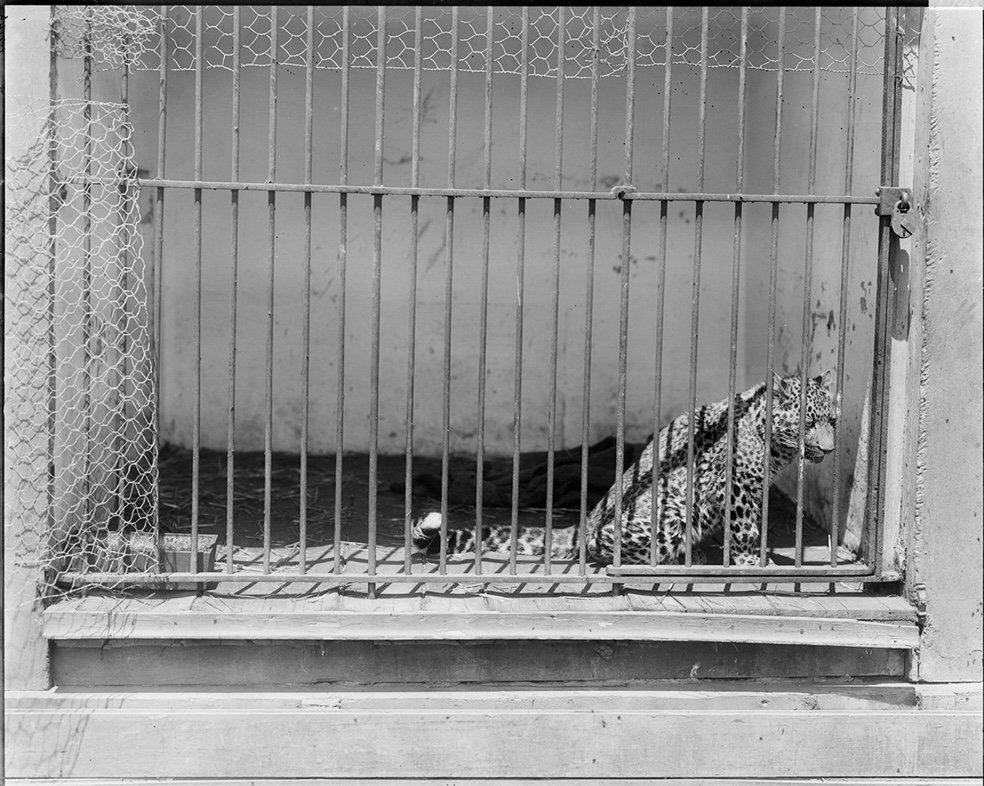

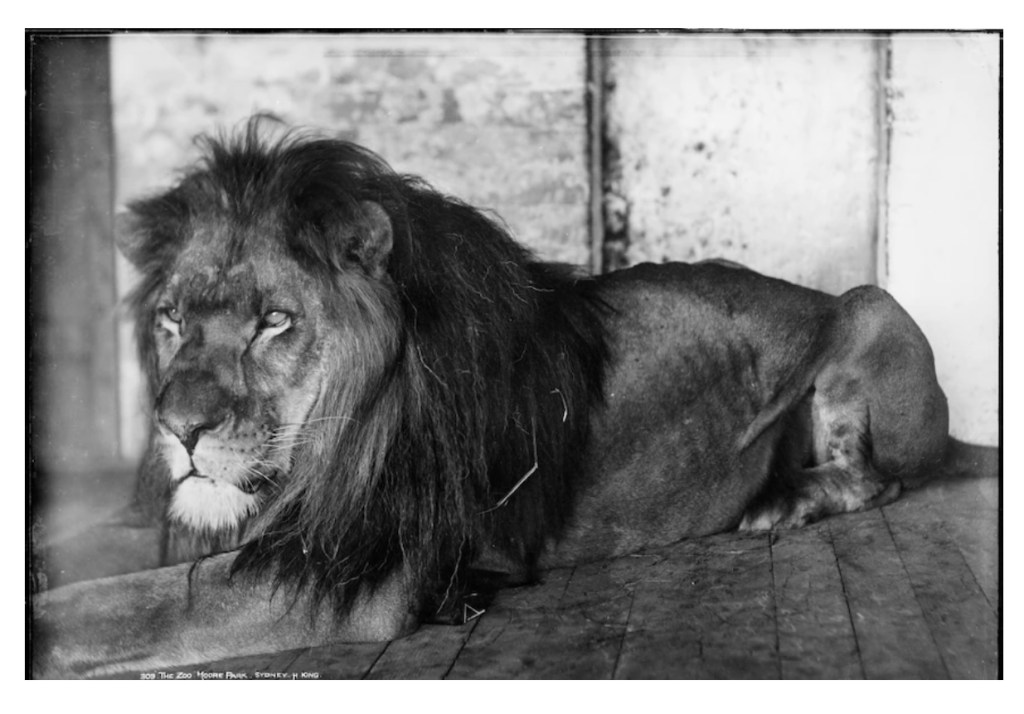

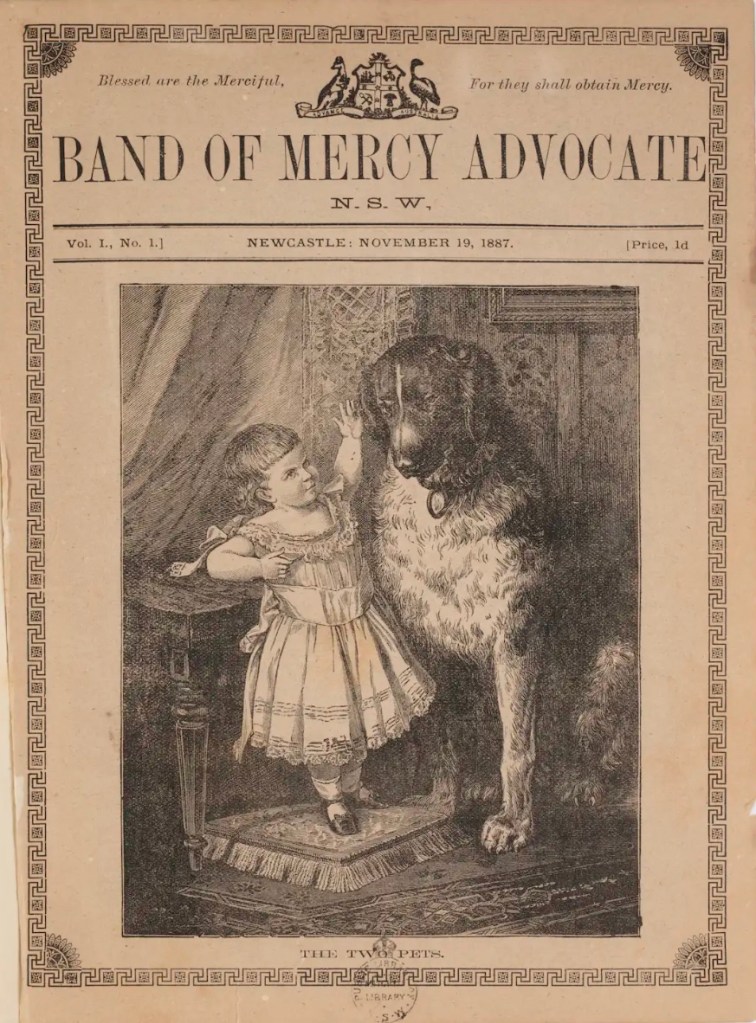

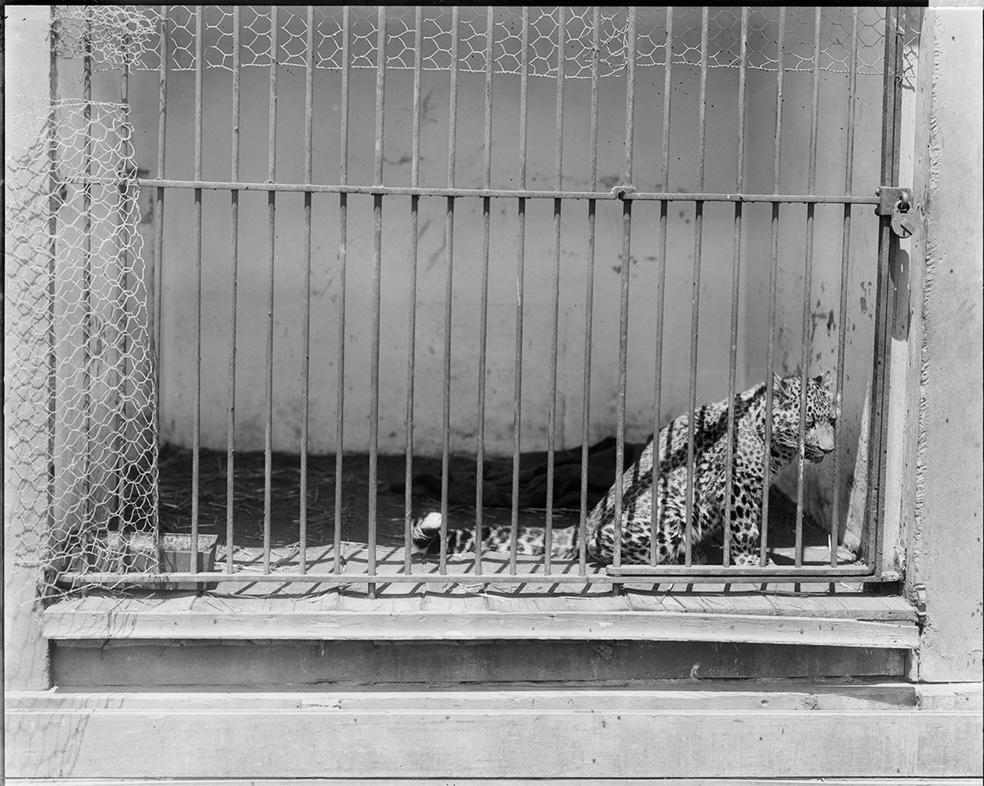

The animal welfare movement was having a most profound effect on people’s feelings about nature, and turned their focus towards zoos. It was the poor conditions under which some 1,000 native and exotic animals were kept at a cramped, three-acre hell at Sydney Zoo, Moore Park, and their obvious distress, that became a hot topic for years.

Dr Le Souef rode this wave emotionally and intellectually. He was a sound voice for animals, and his research and writings underwrote the tenets of this movement that would soon make his dream a reality.

He was Australia’s Dr Doolittle, though a man who did so much more than talk to his animals.

In 1916, with nearly every species represented, a flotilla of once-wild animals crossed a bridge-less Sydney Harbour to a new home on 51 acres of prized Mosman land.

Early life.

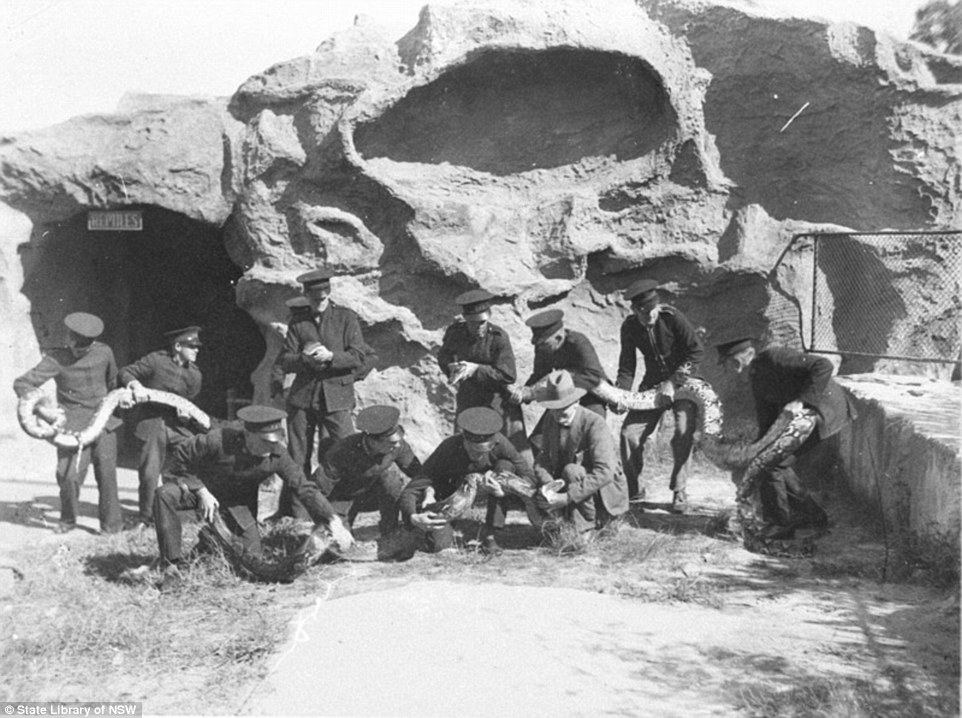

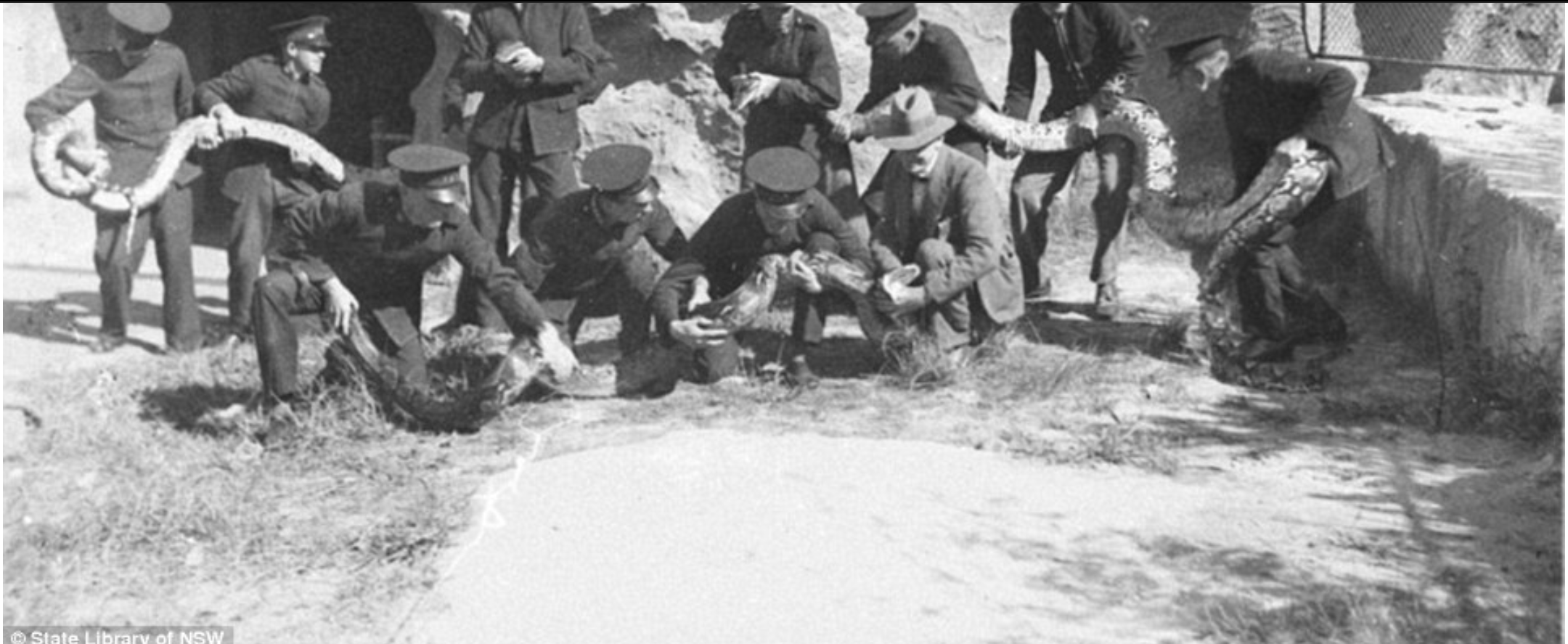

It must have been difficult growing up a Le Souef if one happened to be male. For a few generations, almost all boys were called Albert, and so relied on middle names. They had to have an active love of animals, and be comfortable going about with a jolly great snake wrapped about his personage.

Albert Sherbourne Le Souef was born on 30 January 1877 at Royal Park, Melbourne Zoo, one of 10 children of veterinarian and zoo director, Albert Alexander Cochrane, and Caroline Cotton.

By 1897, and a vet himself, Dr Sher Le Souef (as he was known) became secretary of the Zoological and Acclimatisation Society. After his father died in 1902, Dr Le Souef became assistant director at Melbourne Zoo, before moving to Sydney as director of Sydney Zoo with big and, some thought, quite preposterous notions in April 1903.

Horrified by the inadequate presentation of the 20-year-old zoo, he ran it as best he could while his mission was to search for support to find a site where the animals would not be subjected to dirty, dusty, noisy, soul-destroying conditions.

Dr Le Souef’s dream was for Sydneysiders, and tourists from all over, to have the ultimate zoo, befitting of the nation’s changing attitudes to animals, and worthy of a great city. His zoo would be there for traditional entertainment to pull crowds and cash, and backed by generations of zoological knowledge, they would begin an emphasis on research, conservation and education, which continues today.

The NSW government was amenable, but Dr Le Souef loudly opposed its slated Wentworth Park, Glebe location, in favour of a more suitable site at Mosman. However, Mosman Council and a growing band of residents didn’t want the zoo. Persistence, laced with plan modifications, found agreement so long as the southern flank of the zoo had a thick, tall, concrete wall that would, as was the biggest worry, muffle the lions’ roars. With Council happy, and after a chat with his brother Dudley, he gave the new zoo the name Taronga – an Aboriginal word for ‘sea view’.

The address was simply ‘Rakura’, Mosman. A fuller address might have read: ‘Right up the back, encircled by the deer, antelope, and reptile enclosures’.

It would be some years before the animals would relocate. In the meantime, Dr Le Souef married Mary Greaves on 22 April 1908. They lived at ‘Cooyong’, Bradleys Head Road, Mosman awaiting their new home’s completion in 1916, situated at the rear of the zoo. The address was simply ‘Rakura’, Mosman. A fuller address might have read: ‘Right up the back, encircled by the deer, antelope and reptile enclosures’. Zookeepers lived in huts along the perimeter.

Dr Le Souef, in keeping with family tradition, lectured often, travelling overseas to learn, explore, network with like-minded folk, sometimes to collect or swap animals, and to establish influential contacts.

He was a prolific writer for newspapers and journals, co-authored The Wild Animals of Australasia (1926), and pushed for fauna and flora reserves.

Research on Le Souef reveals a wealth of academic information, but as to the man, little is known and photographs are rare. Perhaps he was someone who preferred the company of animals.

After gaining qualifications in psychology, he posited that the psychology, hierarchy, and spirituality of animals was near-identical to humans; especially reactions to different stressors and pleasures.

But, he caused quite the stir – and got people thinking – with his Radio Weekly broadcast in 1934. After gaining qualifications in psychology, he posited that the psychology, hierarchy, and spirituality of animals was near-identical to humans; especially reactions to different stressors and pleasures. Moreover, he talked about the intelligence of ants, citing two recorded instances of naturalists observing ant behaviour wherein they blocked the ants’ usual access, causing the ants to regroup and rethink. In one case, the ants dug more tunnels under tram tracks when their usual tunnels had been blocked. In another, ants marching through a window were stopped by placing a strip of fly-paper across the sill. The ants left, but returned with sand and splinters of wood, then built a causeway across the strip of certain death.

Better-than-best practice.

Dr Le Souef scoured the earth for best-practice zoos, seeking ways to ‘do better’. Some German zoos had animals roaming in created environments loosely mimicking their natural habitat, albeit with lots of concrete.

He found a spot in Sydney that wouldn’t need an overload of fakery – the rugged landscape of coastal Mosman. There, he would look at moats to separate people and animals, rather than the ubiquitous high fencing. Better still, his proposed location would save Curlewis artists’ camp from overdevelopment when it became part of Taronga Zoo.

Lobbying politicians and authorities for years; giving lectures, media interviews; and bothering influential people had at least given him a profile. Soon, the diplomatic pressure would pay off. His menagerie of a thousand animals would be on the move to Mosman into a world’s best-practice zoo.

In 1912, he was granted 43 acres, and a further nine acres in 1916.

Retirement

Dr Le Souef’s retirement came suddenly and most unexpectedly, and under a black cloud of grief, just weeks after the zoo’s mascot, a 77-year-old Asian elephant, died from stomach torsion in 1939. She was Jessie, a most-loved and gentle old girl who’d long ago stolen his heart.

Perhaps less well known is his children’s book, The Brownie Twins, about a pair of ringtail siblings and their adventures. This he published after he retired, aiming to interest a new generation in animal welfare. References to he and his wife having had children could not be found.

“It’s in the blood.”

Dr Anna Le Souef is the great-granddaughter of Sherbourne’s older brother, Ernest, who launched Perth Zoo in 1897. Dr Le Souef’s great aunts would tell her stories about their father, including how he’d go about his afternoon rounds in a top hat and tails. Or, how they’d open a warm oven to find a pile of snakes.

“One of my great aunts went with her dad to pick up a shipment of animals and they travelled home in the back seat of the car with a pair of flamingos,” Dr Le Souef told Vet Practice in 2014.

Dr Le Souef could not speak to Sherbourne.

“All I know is that I had a relative who died in 1951. “I wish I knew more of those family members from that era. Unfortunately, Sher died thirty years before I was born.”

Dr Le Souef’s ancestors’ magnetic attraction to animals has claimed another generation.

Leave a comment